Ashland Must Go (Partially) Solar by 2020

Progress on the 10×20 Project?

Part 1 of 3

Last week several members of the renewable energy advocacy group, Friends of 10 by 20, met to respond to questions about the 10×20 project with special regard to progress. Participating in the conversation were 10×20 Steering Committee members Andy Kubik, Dave Helmich, Barbara Comnes, Louise Shawkat, Jeff Sharpe and Mary Cody. The interview is presented below with light editing for readability.

Interviewer: Would you please remind us what ‘10×20’ is?

Friend: 10×20 is a law that was passed by the City Council in August 2016 in response to a petition which 4,500 citizens of Ashland signed. The law requires the City to replace 10% of its current electricity use via new, clean, renewable methods by the year 2020.

Interviewer: Where does Ashland currently get its electricity? What is the benefit to the environment of this project?

Friend: The idea is to replace just a small fraction, 10%, of our current electricity use with locally produced electricity from clean, renewable sources. Ashland relies on power sold to it by the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA). This is mostly hydroelectric, clean and renewable. But it arrives at the City contaminated by nearly 50% carbon-generated power because it travels over 300 miles through the Pacific Power transmission system. 10×20 would clean up this small increment of our usage with locally sourced carbon-free electricity while initiating Ashland’s movement toward a more modern and resilient electrical supply.

While it is just a small increment of our usage, it is a substantial undertaking monetarily and technically. But it is a first and important step.

I’ll try to keep this discussion to the actual 10×20 Ordinance execution and save the resilience motivations for another session.

Interviewer: Who supports 10×20 and why should Ashland citizens be interested in 10×20?

Friend: Well, based on the ease with which we gathered the signatures it is the spirit and the sense of our citizens, as I interpret it, to take part in the ‘Great Transition’–the switch from carbon-based energy sources to renewable, clean sources. The Mayor and City Council are clearly supporting it.

Interviewer: The infrastructure needed for implementation: How will it be put in place; How will it be paid for; Who will pay?

Friend: Well, of course that is not covered in the ordinance the Council passed. The typical way people pay for electrical investments is through their rates and over time.

Interviewer: Will the City’s contract with the BPA be impacted by 10×20?

Friend: My understanding is the contract is amendable. It is part of the 10×20 project to work out the BPA contractual issues. My personal take on this would be that if the City can’t make favorable arrangements with BPA, we should not proceed.

Interviewer: How will 10×20 affect Ashland electric rates?

Friend: Well, until Ashland actually selects and financially commits to a renewable energy system to fulfill its 10×20 commitment, we can only “guesstimate” rate effects. Assuming the City is indeed able to enter into a viable, acceptable project, the first 5-7 years might see a slight rate increase associated with — but only with — the 10% of a resident’s power that 10×20 represents. Note again that 10×20 only affects 10% of Ashland’s power.

That said, a slight and temporary increase might be anywhere from .5 to 2 cents per kw hour for that 10% of your total monthly usage–temporary because we know regular power rates that we now pay will surely increase. Standard rates always increase. The City’s solar project rates however will not increase appreciably; these are long-life solar panels with more or less constant (over their useful lives), warranted output. The fuel for the power plant, sunlight, is free.

The result is that after a few years (say 5 to 7 years), the solar 10% of Ashland power will be less per kWh than the standard City rates, and every resident will pay slightly less than it would without the solar farm. In any case, before any large financial commitments are made, the City Council will be required to approve them. The free market, tempered by the judgment of the City Council, will determine the acceptability of any increase in rates.

For those who like easy math problems, merely add a possible maximum increased solar rate of an additional 1 cents per kWh for 10% of say 1000 kWh for a month’s use, and you will see that the pre-tax increase is $1.00 for that month!

Interviewer: Will 10×20 address land use concerns?

Friend: I think land use is a very critical concern–especially in the case of a solar farm. I also think the objectives of 10×20 are very much aligned with other conservation and recreation issues. We are talking in this instance of solar on City owned land–the Imperatrice property–about 50 acres (6 % of that site). I further believe we can find a land use arrangement that will be acceptable to all interested parties. In the case of the Imperatrice property a sparrow species is reportedly locally unique and at least partially occupies the site. Some hiking and equestrian trails have been proposed. There may be rare plant species. There are likely other issues and they absolutely must be taken into account. The site is 850 acres so there should be ample flexibility. An environmental site assessment is on the list of activities for completion prior to issuance of the RFP. We expect it will be carried out in conjunction with possible siting options for the solar array being proposed.

Part 2, Next Week, February 13th

Ashland Renewable Energy Ordinance Part 2

In Part 1 (Nov. 2, 2016), I discussed some of the whys and wherefores of Ashland’s 10×20 renewable energy ordinance project. Now we can discuss its economics and financing. There are three nice surprises: the project is essentially free, the financing of it is relatively easy, and it is entered with no risk at all.

The project, now seen as a 55 acre solar farm across I5 on City-owned property, has a capital cost of millions of dollars which neither Ashland nor any of its residents ever see. There is no debt incurred. Rather, a private company undertakes all aspects of building, financing, and operating the project, and obtains its return by selling the solar power to us. This is called a power purchase agreement (PPA) and it is the standard way public utilities acquire large energy projects. This works because companies can use tax incentives and depreciation. Cities cannot. This is why I say the financing is easy.

PPAs typically retire in twenty years. Then the City takes full ownership with no further obligations, receiving its 22 gigawatt-hours per year free. During the ‘purchase’ period, Ashland will agree to buy the power at a wholesale ‘cents per kilowatt-hour’ rate, if we like the proposal. If there is no proposal the City likes — we stop right there, with nothing spent. This is a City Council decision, informed by the public. This is why there is no risk: we know with certainty the full cost going in.

The project proceeds through a formal RFP (request for proposals). Ashland writes this proposal, and puts it out for bids. A well-conceived and well-written RFP will attract several companies, and hopefully at least one proposal will interest us.

We determine whether a PPA is in our interest by comparing its ‘cents per kwh’ rate to what we pay now (wholesale) for our electricity. Because solar energy projects have burgeoned throughout the world, solar farms have become very reasonable. For example, Tucson has just been offered a PPA for a 100 megawatt system at 3 cents per kwh! Even in the NW where the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA) can sell us power at 4.5 cents (wholesale), solar is competitive. Ashland, developing a smaller 14 megawatt system further north, will expect to pay a little more than 3 cents/kwh.

We can estimate how the solar farm, producing 10% of the City power, will affect our actual utility bill. The PPA offers may range from ~ 5 cents/kwh to ~ 9 cents/kwh. And we can include the possible BPA contract penalty called “Take or Pay”, which could add another 4.5 cents/kwh in the first few years (I will explain in Part 3). These prices will result in an initial addition to the typical utility bill, ranging from a low of ~1.5% to a worst case scenario of ~ 4.6%.

These increases, however, diminish over time since the cost of the standard 90% of Ashland electricity will always increase due to inflation. Before the PPA runs out, its price/kwh will likely be less than the cost of BPA power Ashland buys. Utility bills then see a % decrease, due to the solar. And when the PPA ends, the solar portion is pure free power into the City, and any previously accumulated outlay is very quickly returned.

The purpose here has been to show how the Ashland solar farm is financially sound. The reasons for the ordinance itself however are not to save money. Rather, it is close-up action of significance, taking an actual step against climate change — at the community level. It is offering every person in town, regardless of circumstance, some direct participation in the transition away from fuels with greenhouse gas emissions. It is Ashland making a strong statement.

In Part 3, we explain the BPA Take or Pay issue and give possible resolutions of other perceived hurdles in moving forward in a community clean energy project.

Tom Marvin, Prof. Emeritus,

Physics, SOU 1976-2006

Why Won’t Ashland Embrace Solar Energy?

10×20 Project Report June 15, 2019

A Focus on Renewable Energy, CEAP, Resiliency, and Higher Value Solar.

Background

The 10×20 steering committee summarizes here the progress made in the project over the last few months. We offer in brief the main elements as we see them, and invite input and support in behalf of your interests in the development of local renewable energy due to its role in climate action. The ordinance calls for the replacement by the City of Ashland of 10% of its electric energy use by new, local renewable means, by 2020. This amounts to ~17 million kwh per year, or 17 gwh/yr.

Consideration was given to a number of methods to achieve this goal, and it is well-determined that we can probably only accomplish this via a large solar farm utility operated by the City. We also discuss why several often-suggested alternatives are in fact not considered attractive.

Sample Field Array

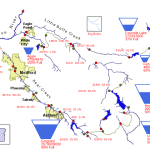

One factor suggesting the solar farm solution is the availability of an existing site already owned by the City. Significant work has been done in 2016 – 2018 by Ashland to determine the suitability its 846 acre Imperatrice property as a possible site for the required 60 acres. The standard financing of such a project is through a power purchase agreement with a 3rd party investor, where the full cost to the City is met through its sale of the PPA electricity to residential and business customers via the standard City rate structure.

Reiterating the Fundamental Purpose of 10×20

The spirit behind the 10×20 ordinance is primarily the pursuit of community climate action, very much in line with the City’s CEAP goals. This is to be achieved by producing approx. 17 gwh/year of very clean electricity, freeing that much BPA electricity (our wholesale supplier) for use wherever its own clean energy can be purchased by other customers. The net result is that 17 gwh/year of clean energy is pumped into the NW, ultimately displacing that much non-renewable energy. We note that GHGs are a nonlocal toxicity; reducing it anywhere is identical to reducing it anywhere else; it is always and only a global action.

A secondary purpose of 10×20 is the production of energy for use in local resiliency. This is made possible by the project steering committee’s call for:

- battery storage for both solar peak-shifting and moderate-to-low level storage use in times of outside power loss, and

- an upgrade of the City’s Reeder Gulch hydro plant for seasonally balancing renewable energy sourcing with the solar farm, and for its 24/7 energy supply sourcing during outside power loss.

It is the addition of a Reeder upgrade that enables 10×20 to support a 10Mw solar farm instead of a 12-13 Mw solar array. This is especially significant because it enables the solar farm power to be handled directly by two existing substations without upgrades, per the City’s OS Engineering study report.

When we identify resiliency as a sub-purpose of 10×20, the emphasis is directed at the micro-grid function, and the local sourcing for it which the renewable energy offers. Having the dual capacity offered by the solar farm and the hydro upgrade (along with the battery storage) gives Ashland an excellent energy supply for the micro-grid. The micro-grid, with these supplies, is a complete but small utility unto itself capable of operating a large fraction of Ashland’s emergency electrical requirement — without external power.

The Financial Picture in June 2019

The current understanding of the costs involved in completing the project as described herein and elsewhere can be enumerated.

1. The solar farm cost per kwh to customers may be slightly higher than current BPA wholesale prices, but lower than Ashland’s current retail to customers. The impact is small since the solar component is still only ~8.5% of the mix. It can be shown that the increments in the monthly electric costs are less than the already planned City increases for next year. Over time (6-8 years or less), the BPA wholesale rates to Ashland will exceed the solar PPA rates. After 15-20 years the PPA rates will drop to zero, when the City then owns the solar and after which we can expect decent output for another 20+ years.

2. We do not know the costs of the Reeder hydro upgrade, but we expect likely assistance from grants. Reeder has been in operation over 100 years and will continue indefinitely.

3. Battery storage recommended here [to be refined by engineering] is in the vicinity of 2 Mwh capacity and 2 Mw power since its primary use is minor solar peak-shifting. Battery storage has become cost effective nearly as fast as solar pricing has dropped. (See the Lazard Levelized Cost of Energy report1). Cost: approx. $350K.

4. Micro-grid development. 10×20 does not include this work, but aims to enable it.

5. The 7 years of a possible BPA Take/Pay liability has been a main concern by the City and others. We have approached this directly, and City officials then met with Bonneville Power to clarify the consequences of Ashland generating 10% of its power with new resources, ahead of its contract renewal in 2028. Results: To the extent that the City energy usage drops beneath its RHWM2 (due, say, to 10×20), BPA can levy charges for the difference between its wholesale rate to Ashland and the current NW spot market prices. We [10×20 steering committee] have analyzed this in depth by examining average spot market prices over a five-year period. We do not observe, in a worse case scenario, discouraging results. Two other factors are in play with this: contract accommodations in 2028, and (hopefully) increased natural use of electricity by Ashland for heating and electric vehicles charging — as proposed by our CEAP commitment. Increased use of electricity directly reduces the RHWM gap caused by the 10×20 production — which directly reduces the amount of power and cost associated with Take/Pay. We will bring some highly useful spreadsheets with these results to our next 10×20 meeting.

Understanding Utility Solar vs. Rooftop and Community Solar

The most persistent question among alert citizens that arises as interest increases in climate action via renewable energy use is “why not just double down on rooftop solar?”. Another version of this question is “why not one or another exotic plan using community solar?”. There are very solid reasons why not that we can point out here. Again, it is easiest to enumerate them:

1. Utility solar is less than half the cost of all other solar pv applications3.

2. There are limits to the ability of a utility (Ashland Electric) to support net-metering with payback for into-the-grid power generated by rooftop solar.

Each kwh of private solar reduces City revenue while not reducing the Electric Dept.’s grid maintenance obligations. Expanded net-metering will eventually saturate, with obvious fiduciary results. The grid is financed through income from power the City sells to users.

The impact of net-metered City revenue losses tend to force rate increases for all residents and businesses simply because fewer people supporting the utility grid means its expenses are spread across fewer customers. In other words, roof-toppers, to an extent, are in fact partially supported by residents/businesses who do not or who cannot have rooftop solar. Community solar, which is a misnomer, has exactly the same effect.

In comparison, the City owned/operated solar farm is in effect an electric co-op enabling every single person, even visitors to Ashland, to automatically participate in our expanding solar world. Everyone in the community contributes to the climate action. [If necessary, there could be an opt-out mechanism.] Instead of costing the City revenue, this utility gives the City revenue.

(We emphasize that while there are community disadvantages to ‘rooftop’ solar, almost every 10×20 advocate has rooftop solar or fully supports it. There is nothing in the 10×20 project development that discourages anyone from pursuing rooftop solar. It is climate positive but simply not the most cost effective deployment.)

3. The City hosts approx. 2.2 Mw of net-metered roof-top solar, which is ‘very good climate action’. This has cost Ashland approx. $925,000 in incentives plus its losses in revenue described above. The large presence of existing roof-top solar in Ashland could in principle also supply a future micro-grid. However, the distributed nature of rooftop would make this more challenging at this time.

4. There are not enough additional, suitable, rooftops and available, likely spaces for community solar to furnish the energy that a 10 Mw City solar utility will generate.

5. If the 1 Mw solar grant project the City electric dept. is (apparently) currently pursuing is successful, it will serve as a fine component of 10×20, reducing the solar farm level to 9 Mw. It will also have battery storage, with an eye toward a City micro-grid. (Please note that the 10×20 solar farm is in no way in competition with this endeavor. Both initiatives should be fully regarded as helping to fulfill our 10×20 ordinance.)

Obstacles to 10×20 and the Project Off-Ramps

The City has undertaken several necessary steps that 10×20 has required, to this point. These include:

- ordinance adoption,

- a professional power engineering analysis,

- several opposition citizen group testimonies,

- an environmental analysis,

- many meetings with the 10×20 steering committee members,

- many hours of staff analysis,

- preliminary RFP documents for the solar farm,

- the Portland meeting with Bonneville administrators,

- and probably many hours of private discussions.

It cannot be said that Ashland has not considered this project. But while several hurdles have been passed, several more remain:

- Concern for some disruption of the Imperatrice property, which is generally seen as pristine by some conservationists.

- No doubt neighbors and others are concerned about the physical presence of 60 acres of panels.

- The potential short and long term rate affects are not exactly known and will not be until an RFP is issued and proposals are evaluated.

- We do not know whether the land use county/state variances can be obtained.

- We do not yet know whether suitable geotechnical [foundation soils] and acceptable positioning on Imperatrice can be made.

- Finally, many of us think and appreciate that the public will be called upon again to certify or reject the project, after the challenges described here are met.

Each of these present Ashland with an off-ramp by which the solar farm part of the 10×20 project can be derailed. This is the way it should be; we can delight in the realization that democracy is alive and well in our community. We can determine very much our energy directions.

There are many interesting, correlated projects to follow 10×20. For example, we can envision an energy storage co-op organization, again probably City-operated, whereby a large number of eV users network with a system that can on the average depend on a certain minimum amount of total EV battery function furnishing its total charge to the City grid — serving an important load-leveling function as well as another positive micro-grid element.

Dr. Tom Marvin, Professor Emeritus in Physics, Ashland

1,3 www.lazard.com/perspective/levelized-cost-of-energy-and-levelized-cost-of-storage-2018/

2 RHWM is the industry ‘rate high water mark’, and is one billing benchmark among several for understanding not just how much energy a utility uses, but also it’s change, in 2-3 year increments. It is compared and adjusted against a contracted CHWM, the ‘contract high water mark’. Take/Pay can be initiated when a utility uses less energy than its RHWM specifies. This can happen under a 10×20 installed resource — until which time the City can obtain a new contract (2028). The RHWM a fluid parameter, but so is Ashland’s energy use. If CEAP becomes successful, our energy use can mitigate some of these effects.